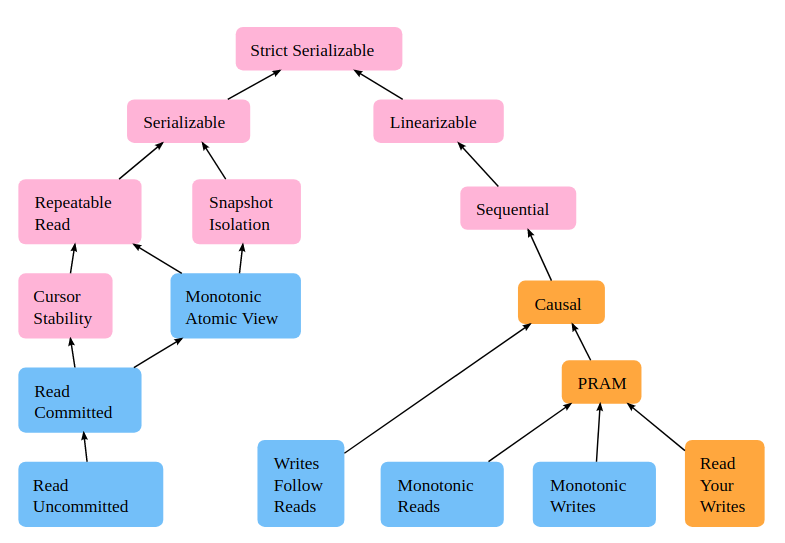

Let’s take a look at this tree of consistency models at jepsen.io.

The arrow means “is implied by”. For example, “strict serializable” implies both “serializable” and “linearizable”.

As for the coloring:

- Pink means “unavailable” during some types of network failures;

- Orange means “sticky available”, i.e., non-faulty nodes continue to be available, assuming that clients stick to the same servers they are already talking to;

- Blue means “total available”, which means every non-fault node is available, even when the network is completely down.

Linearizable versus serializable

Peter Bailis gave a nice summary.

Linearizable: single-operation, single-object, real-time order.

Linearizability is the C in the CAP theorem. It means writes appear to be instantaneous, i.e., atomic consistency. However, it does not care about transactions.

Serializable: multi-operation, multi-object, arbitrary total order.

Serializability is about transactions. It is the I (Isolation) in ACID. It guarantees that a set of transactions (over multiple items) is equivalent to some serial execution (total ordering) of the transactions. You cannot interleave sub-operations between transactions. However, serializability does not care about the actual order of transactions. (Note: Order of operations within each transaction should be preserved.)

Neither linearizability nor serializability is achievable without expensive coordination. This implies no full availability. And in practice, systems implement weaker versions of these for performance purposes.

Finally we have strict serializability.

Strict serializable: multi-operation, multi-object, real-time order.

As we expect, it means transactions appear to execute sequentially (serializable) and in addition, the order is not arbitrary, but in the obvious order — whichever transaction arrives first gets completed first.

Linearizable implies sequential consistency

Sequential consistency: single-operation, single-object, arbitrary total order.

Both sequential consistency and linearizability are about single operations. Both sequential consistency and serializability are about existence of some total order which is not necessarily the real-time order. In other words, no matter how you execute the operations concurrently, it is as if there is some order or permutation of these operations across all processors.

Obviously, linearizability implies sequential consistency.

Serializability implies snapshot isolation

Snapshot isolation is a weaker guarantee on transactions than serializability. It is adopted in many databases, e.g., MySQL, Postgres, MongoDB, because it offers much better performance than serializability. It is commonly implemented by MVCC (multiversion concurrency control), i.e., keeping multiple versions of the same value, say in RocksDB. Common point of confusion: In SQL, “serializable” often means “snapshot isolation” only.

Snapshot isolation means that every transaction operates on an independent snapshot of the database. This allows multiple transactions to happen concurrently, based on the snapshots at the start of each transaction. However, if there are conflicts, say transaction 1 needed to modify an object X, but transaction 2 committed a write to X between transaction 1 start and transaction 1 commit,then transaction 1 must abort.

One key feature of snapshot isolation is that when the transaction is done, its changes become visible atomically. (This seems like a basic requirement on transactions!) Hence, snapshot isolation also implies “read committed” which means there are no dirty reads, i.e., we cannot observe writes from transactions which have not committed.

Unlike serializability which requires a total order, snapshot isolation only requires a partial order — sub-operations in transactions may interleave in arbitrary ways as long as there are no conflicts between the transactions.

The most notable problem with snapshot isolation is write skews. Consider the following scenario:

- Transaction 1 reads variable x.

- Transaction 2 reads variable y.

- Transaction 1 writes the value it read to y. (y <- x)

- Transaction 2 writes the value it read to x. (x <- y)

Both transactions have a consistent view of the database and their write set do not overlap. However, we see that the values of x, y have been swapped. Suppose we have serializability instead and say transaction 1 completes before transaction 2. Then everything would be set to the initial value of x. There will be no swapping.

Various databases have some hacks around snapshot isolation to mitigate the problem of write skews. See for example Postgres’ Serializable Snapshot Isolation technique.

Read Committed (total available)

For models like “snapshot isolation”, total availability is still impossible (during network partition) because we need a snapshot which is consistent across the cluster of machines, and maintaining this consistent snapshot requires coordination. To obtain total availability, we can consider a weaker consistency model, the “read committed” model.

The read committed model is a transactional multi-object model. All it says is that transactions cannot observe writes from other transactions which have not committed, i.e., no dirty reads.

However, there is no constraint on the ordering. That means if transaction 1 commits a write to variable X and transaction 2 starts and reads variable X, then the value read by transaction 2 may not be the value written by transaction 1. (If we need to sync the new value of X across all machines, then we will lose availability during network partitions.)

Read committed can be achieved by simply locking on each row / key. There are some obvious problems, e.g., double count, missing count. Say we want to count rows which fulfills a certain predicate. As we scan through rows in a transaction, we lock and unlock row by row, while concurrent transactions may be changing other rows that are not locked. If a row somehow gets shifted after the scan pointer, then it gets counted twice. If a row gets shifted before the scan pointer, then it does not get counted.